Why is it so hard to find a plumber or handyman these days?

C

indy Bouldin has been trying to get a few projects done on her condo since she moved there in April. The 1970s building near Magnusson Park still has its original single-pane windows. She’s hoping to replace them before it gets cold.

Bouldin reached out to about a dozen handymen and contractors. Some never called her back. Others don't see her relatively small job as a priority.

“Everybody's out there doing their other work,” she said. “They're not waiting on me, so I understand that. But it's been months and now I'm not sure the windows will be in before winter hits. It's going be cold in here.”

Bouldin’s situation isn’t unusual. KUOW heard from dozens of folks experiencing similar challenges.

Sponsored

Things appear to be just as tough for employers. In both cases, there just aren’t enough skilled tradespeople to hire. That’s in spite of the fact that jobs in the trades often pay six-figure salaries and don’t require a college degree.

Sponsored

To understand the labor shortage in the trades, it’s helpful to visualize the type of worker that’s missing. Employers say they’re struggling to find experienced workers — that is people in their 30s and 40s capable of picking up jobs like Bouldin’s. Now imagine what opportunities were presented to those folks when they were picking a career path.

When that generation was in high school, there was a significant shift education. In the 1980s and '90s, states started increasing academic requirements students needed to graduate. At the same time, they began decreasing investments in vocational training — classes that exposed students to trades like auto repair and carpentry.

The goal of the shift was to get every student to shoot for a four-year degree. But it caused two unintended problems. First, fewer students saw the trades as a viable career path. Second, trade school took on a stigma.

Justin Richardson is feeling the effects of those missing workers today as the owner of an electrical company in Mukilteo.

“If you don't know someone in the industry already, oftentimes it's just overlooked in general,” he said. “It's not something they discuss in school. It's always mentioned as, ‘Oh, you can go into the trades,’ and it's more of a last resort.”

Sponsored

Richardson has a handful of electricians who have worked for his company for more than 20 years. They’re nearing retirement age and he’s struggling to find experienced workers to replace them.

“There is a significant gap between them and all the apprentices that are coming in who are all in their twenties,” he said.

The pandemic exacerbated the problem. Many older workers retired early. It’s going to take time to rebuild that missing middle, especially as the workforce overall gets older.

There are some indications that this trend could be reversed in the coming years. Richardson is starting to see a spike in applications from young people. Fewer high school seniors are choosing to pursue a four-year degree. The pandemic and student debt crisis have many of them questioning whether college is the best investment.

Sponsored

Marianna Talbott wishes she'd known college wasn't the only option when she was in high school.

“Take my story for example,” she said. “Seventy-plus thousand dollars of college debt for a degree I'm not using.”

That degree was in nursing, but Talbott doesn't work in a hospital. Instead, she's made it her mission to educate people about a different path.

Talbott recruits apprentices to the Northwest Carpenters Institute. It's a tuition-free carpenter training program and graduates can expect to make more than $100,000 a year. Still, she says it’s difficult to recruit young people. The average age of new apprentices entering the program is 28, she said.

“Especially in the Seattle area where it's very tech driven, you've got the Microsofts and you've got the Googles and the Facebooks,” Talbott said. “People look at that and they think, ‘Oh gosh, that's the industry I want —technology.'”

Sponsored

Learning to code can seem like a fast-track to a six-figure salary. Dozens of coding bootcamps have cropped up selling that version of the American dream. They’re a high-tech spin on an old-school model: vocational training.

But bootcamps can cost thousands, while trades apprenticeships are often free. Apprentices are usually guaranteed jobs, and the wages rival the estimated annual salary for a junior software engineer. And many jobs in the trades are less vulnerable to displacement by generative AI.

“That's an interesting conversation I've had with a neighbor who was a manager at Amazon for programmers,” said Richardson, the electrician. “He fully believes that in 10 years, electricians are going be making more than senior programmers just because programmers will eventually program themselves out of a job.”

Of course, tech jobs offer comforts that electricians and carpenters don't have. Tech workers are often able to work from home, at least some of the time. The hours can be less grueling, and the jobs tend to come with cushy perks.

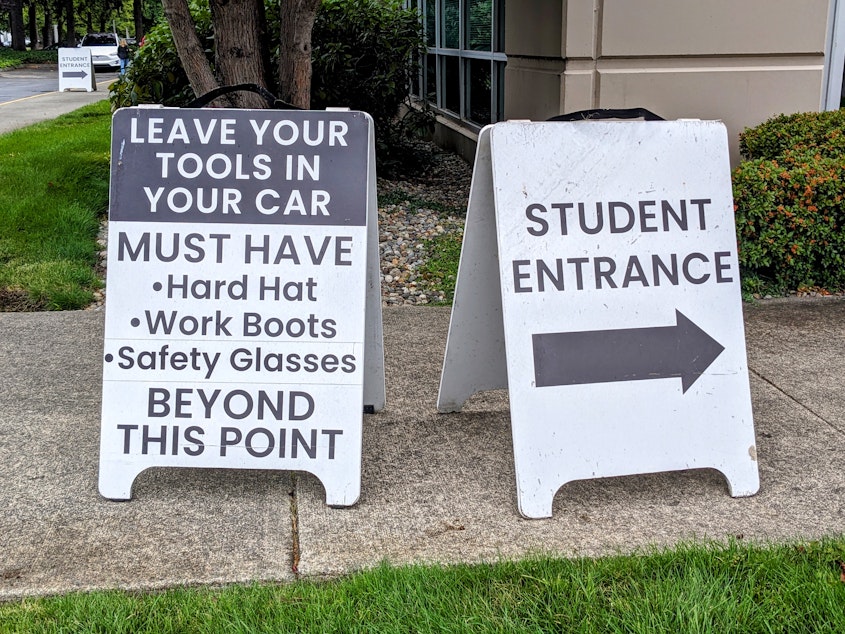

“A lot of times people think, the money's great, that's super attractive, until they realize, it is rigorous, it's physically demanding,” Talbott said, of carpentry jobs. “Sometimes you have to get up at four in the morning just to make sure you get yourself ready, get your lunch packed, to make that commute, to show up to the job site on time.”

Sponsored

It might not always be glamorous, but these jobs do offer steady work and a living wage. In a fast-growing city and ever-changing economy, that might be enough to finally bring workers back to the trades.