Woolly dogs once provided fleece for Coast Salish tribes. What happened to them?

For centuries, woolly dogs have been at the center of tribal life throughout the Coast Salish world.

Since the 19th century, however, these dogs have been considered extinct. Today, a resurfaced specimen at the Smithsonian Institution is helping broaden our understanding of the woolly dog's genetics and role in Coast Salish life.

"Where I'm from on Vancouver Island, we didn't have mountain goats or sheep or anything like that. And so instead, we had these little fluffy dogs that we shared to use their hair as fiber and weaving," said Eliot White-Hill (Kwulasultun) from the Snuneymuxw First Nation in Nanaimo, British Columbia.

Among Coast Salish nations, stories of woolly dogs have been handed down since their extinction in the 19th century. Inspired by those stories, White-Hill crafts a range of artworks and is currently working on a children's book based on a traditional woolly dog story. It involves the mischievous raven, who in a complicated ruse, managed to trick woolly dogs into swapping their derrieres.

"And so that's why dogs sniff each other's butts — they're trying to figure out if it's theirs or not," he said. "It's so cheeky... no pun intended. The humor is what I love."

Outside of alpacas, woolly dogs were one of the few indigenous animals providing wool in the Americas. Among the Snuneymuxw First Nation, high-ranking women took care of the dogs, and the canines were even given special treatment like their own private island and a hearty salmon diet. Woolly dogs were given this treatment because weaving was revered, and these dogs played an instrumental role in the craft: their hair was the raw material for blankets and wool coverings.

"Traditionally, the blankets are almost like a currency to us," White-Hill said. "They're like nobility blankets, so they're major symbols of wealth. And to us, through a potlatch you become wealthy by giving away, which is kind of at the core of our culture and our socio-economic systems. The significance of the blankets and the value brought to our communities through their weaving them through the fibers that are used — it can't be understated."

Sponsored

Rediscovering mutton

Despite their disappearance, indigenous tribes have handed down their knowledge and customs around woolly dogs. However, there was little scientific data about their fate.

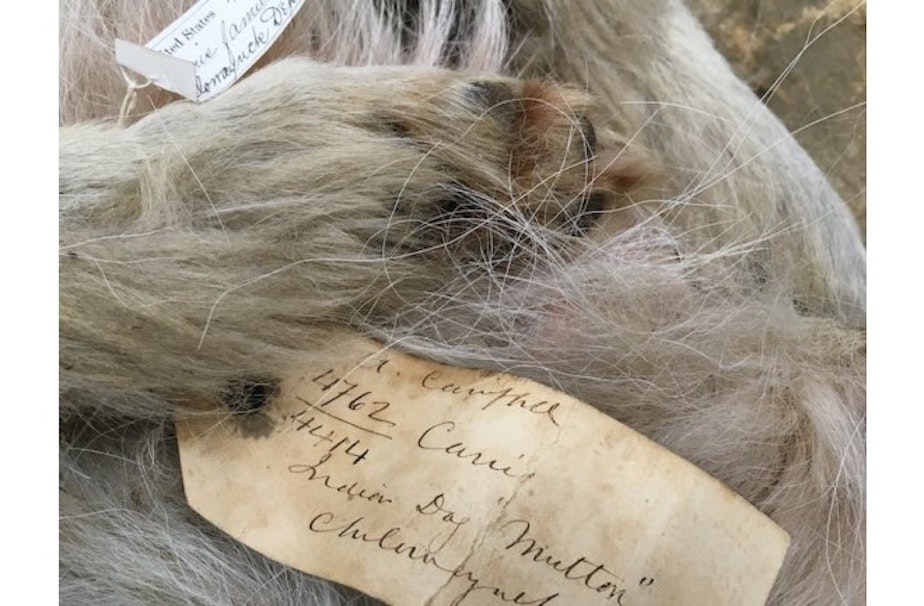

That all changed recently. For 160 years the Smithsonian Institution has been holding onto a woolly dog pelt deep in its archived collections. That dog is called Mutton.

Scientists have recently taken an interest in what Mutton's pelt can tell us about the genetic makeup of indigenous pre-colonial dogs.

"There were concerted efforts by the colonial governments to assimilate the indigenous peoples, and to criminalize cultural practices," said Audrey Lin, research associate in anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution. "And a lot of the cultural practices, the knowledge, it went underground. It was performed in secret. But it's really hard to keep dogs secret, so they were one of the first casualties of colonialism in the area."

Sponsored

Mutton's pelt was added to the Smithsonian's collection in the 1860s. He became the personal dog of George Gibbs, a naturalist, explorer, and ethnographer sent to the region as part of the Northwest Boundary Survey, which mapped the boundary between what is now Washington state and British Columbia.

As part of the survey, he would regularly send wildlife back to the National Museum in Washington, D.C., the precursor to today's Smithsonian. An entry in Gibbs' diary from December 1859 notes that Mutton was sick, and after he died, the pelt was sent back East.

"It's to our benefit, because Mutton's the only known woolly dog pelt that we have," Lin said. "So if Gibbs hadn't done that in late 1859, early 1860s, then there still would be a lot of mysteries about woolly dogs."

With Mutton's pelt, scientists at the Smithsonian have been able to glean insight into the genetic makeup of pre-colonial dogs, or PCDs. These dogs were reproductively isolated from general dog populations, meaning they were genetically unique.

Sponsored

Lin was interested in seeing what kind of genotypical and phenotypical characteristics were unique to woolly dogs, including why their hair could grow to the point where it could be shorn. Mutton shares a lot of characteristics with spitz dogs like Samoyeds, Siberian huskies, and malamutes — though the dogs aren't closely related breeds despite their similar appearance.

Mutton's genetic makeup was shown to be 85% pre-colonial dog, with 15% made up of introduced European settler dog, which were likely introduced within a few generations of Mutton.

From there, researchers have begun using what's called a "two eyes seeing lens" to have a more holistic view of the history and the anthropology of Mutton. Through interviews with Coast Salish tribes, Smithsonian researchers have confirmed that woolly dogs' unique genetics are due to centuries of tribal breeding practices.

"If we had just sequenced Mutton's genome, we would have been able to learn things about his ancestry, we still would have identified the genes, variants associated with wooly hair with hair follicle growth with skin," Lin said. "But we wouldn't have really understood why — why these dogs were so different."

Sponsored

Lin said that despite living in a scientific era where cloning technology exists, it's unlikely that woolly dogs could be brought back from extinction.

"For example, de-extincting the woolly mammoth — it's not really cloning a mammoth or bringing them back literally, it's more augmenting the genome of an Asian elephant so it looks like a woolly mammoth," Lin said. "It'd be very expensive, and I don't think it would be a realistic approach for bringing back the practice of keeping woolly dogs."

Even as woolly dogs have disappeared, Coast Salish weaving has continued. Michael Pavel, from the Skokomish-Twana Indian Nation, said that a renaissance in traditional wool weaving has grown the weaving community from a handful of people to thousands. In this case, weavers are using traditional looms with non-woolly dog fibers, like mountain goat fleece.

"It is so easy for us to fall back into a terminology that says we raised, we bred these dogs for their wool. But they were relatives, and we cared for them," Pavel said. "They taught us several important things that are always essential to our humanity, and that is we need to work together. We're good individually, but we're so much better together."

For artist Eliot White-Hill (Kwulasultun), the story of the woolly dogs gives a nuanced view of life for Coast Salish people.

Sponsored

"It starts to break down people's understanding of us as a hunter-gatherer society, which is such a simplistic, blanket understanding of Indigenous people in general here in North America," he said. "That I think is really where the the work of reconciliation can be done. It comes from understanding and empathy, and knowing that sense of understanding is a place where empathy can flourish."

Audrey Lin, at the Smithsonian, said the institution's work on collaborating with Coast Salish knowledge keepers on understanding the woolly dog is valuable — and ongoing — work. She pointed to Coast Salish blankets that, like Mutton, have been preserved in museums across Canada and the United States.

"I think this is just like a really good example of the uneasy tension that these old museums with these massive collections have with communities, with countries that had been colonized and plundered," she said. "It's an uneasy relationship, but I am hoping that it is possible to be able to work and collaborate with the descendant communities. We definitely have a responsibility to move towards reconciliation,"

Listen to the full Soundside segment by pressing "play" on the audio icon above.