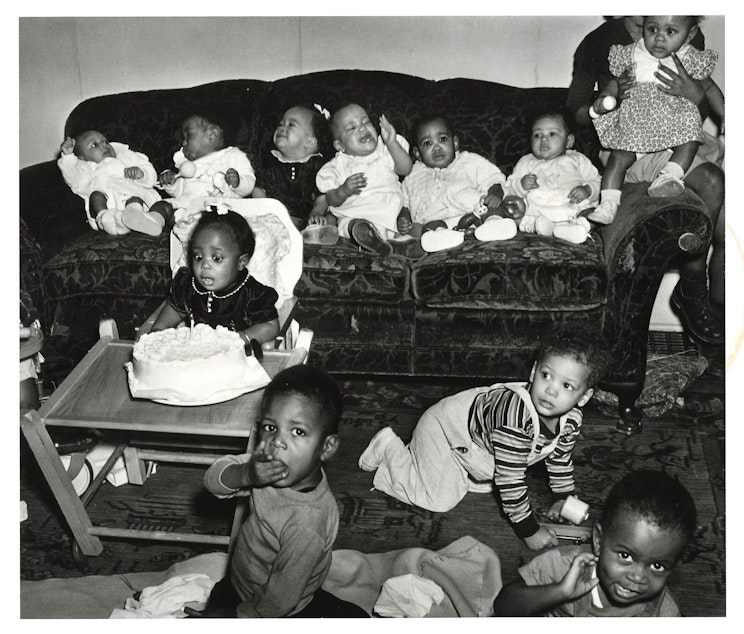

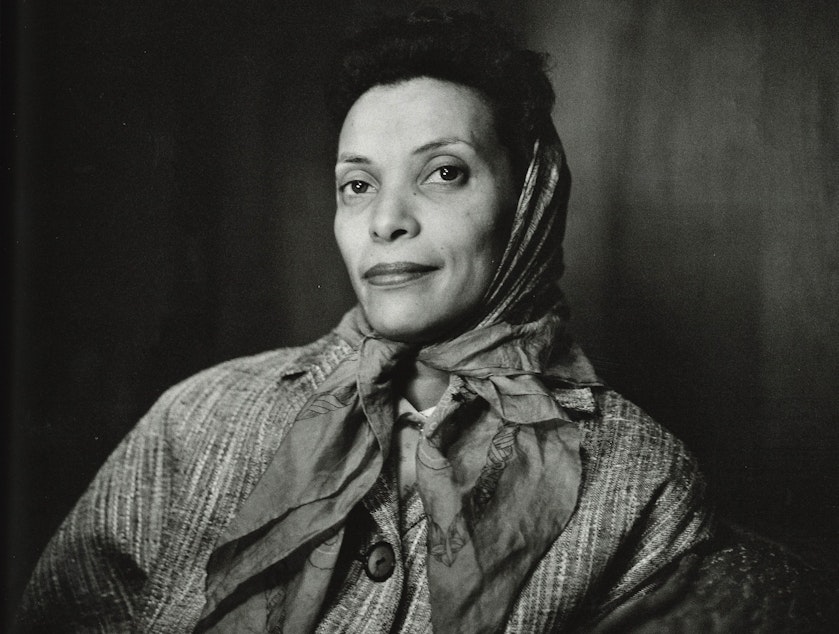

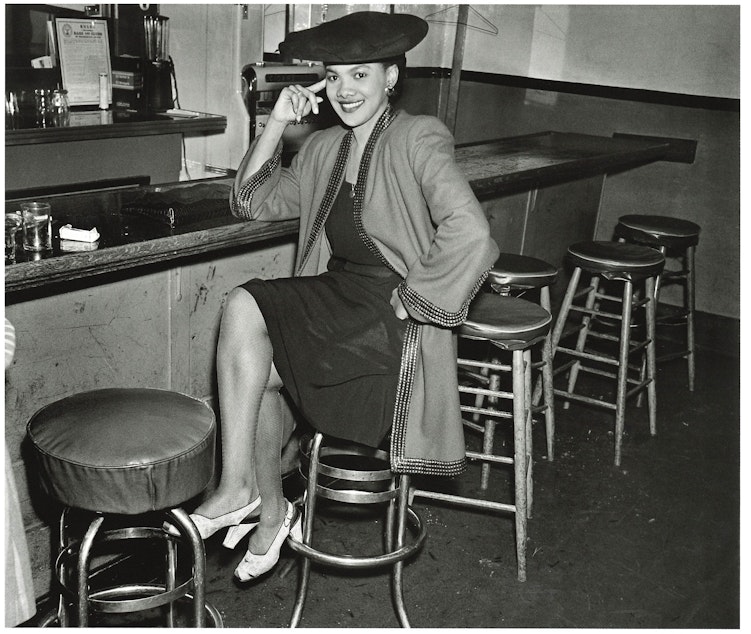

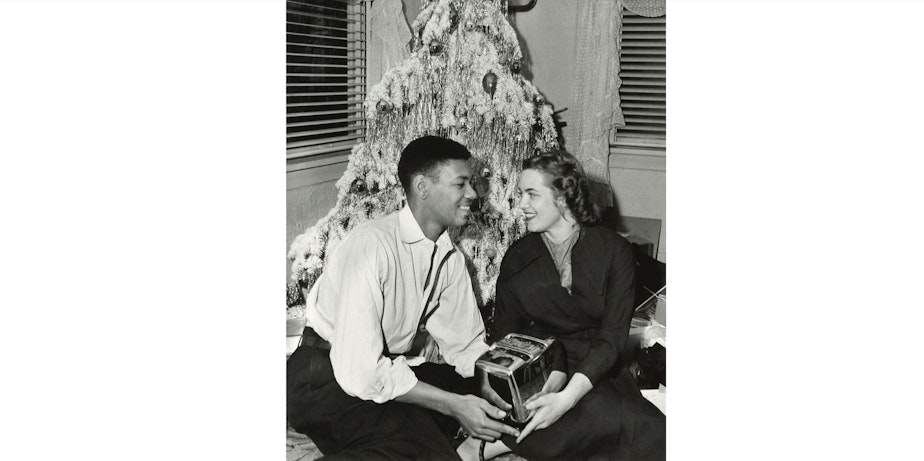

Old photos of Black Seattle delivered in boxes: Help us ID them

After Al Smith, a street photographer in Seattle, died in 2008, his children donated 40 boxes of his photographs to MOHAI — the Museum of History and Industry.

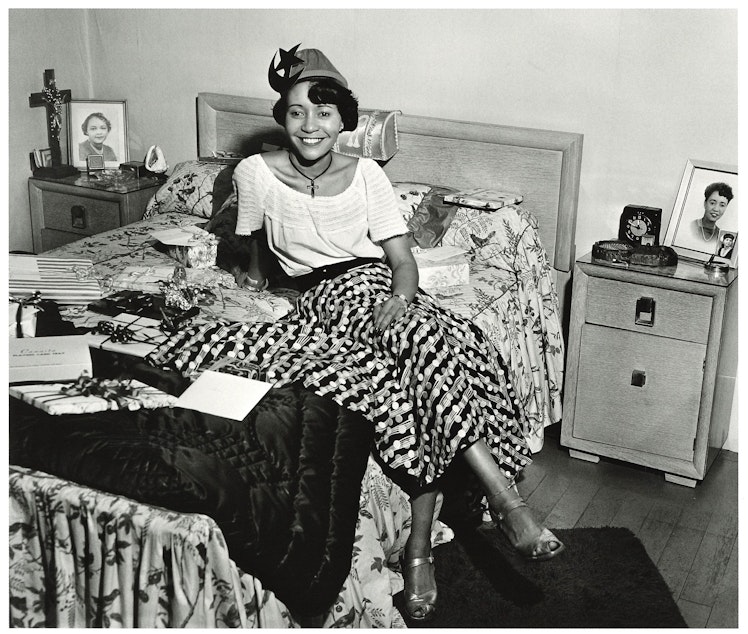

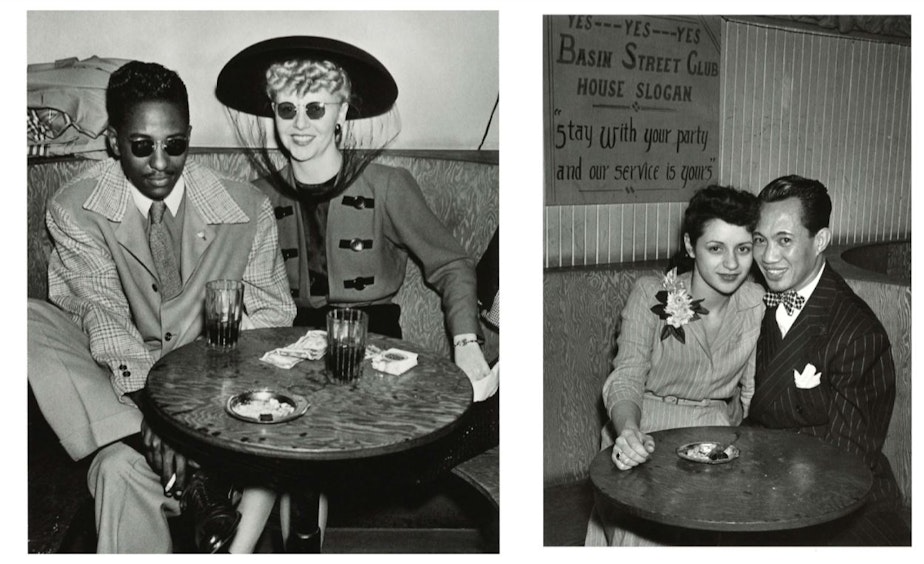

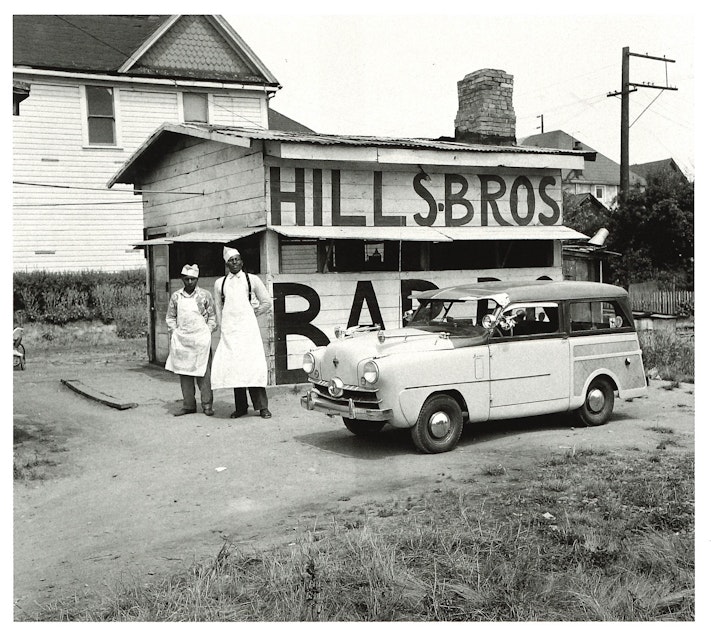

Many of these photos are of unidentified people. If you know them, please let us know so we may update these captions.

When Al Smith came of age in Seattle’s Central Area, the neighborhood was the heart of the Depression. Smith’s family didn’t have a lot of money -- nobody did.

Sponsored

“His first career move was to jump on ships,” says Howard Giske, former photography curator at MOHAI, in a 2015 interview. “As he told it to me, this is what got him inspired about photography.”

Giske says Smith traveled the world and wanted to have a record of what he saw. By the time the young man returned to Seattle, he had a professional camera and carried it everywhere.

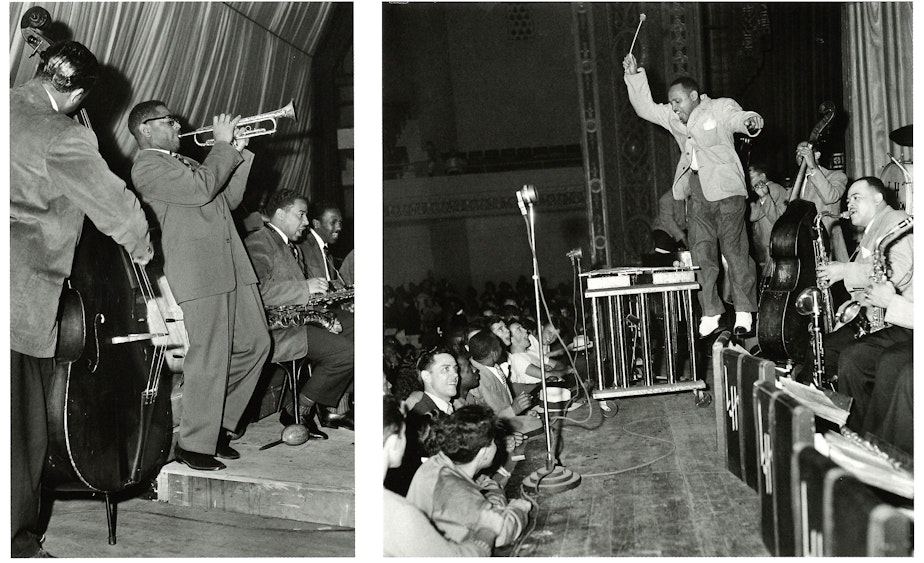

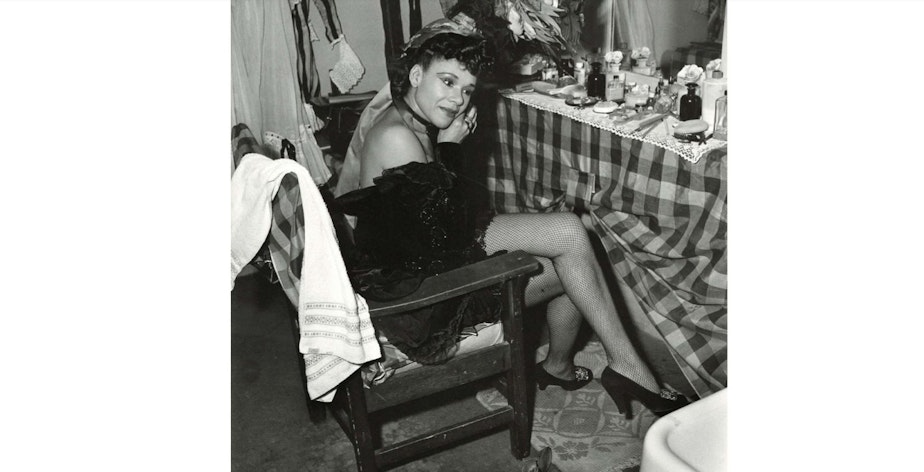

“He said I could get into any situation with that, I could cross police lines, I could get past the club security.”

Sponsored

But Al Smith wasn’t a professional photographer the way we think of that term these days.

“It was a side job for sure,” Giske says. “During the war years he worked at the shipyard in Bremerton, later at the Post Office. The photography was something he had to at least make it pay for itself, I think.”

Sponsored

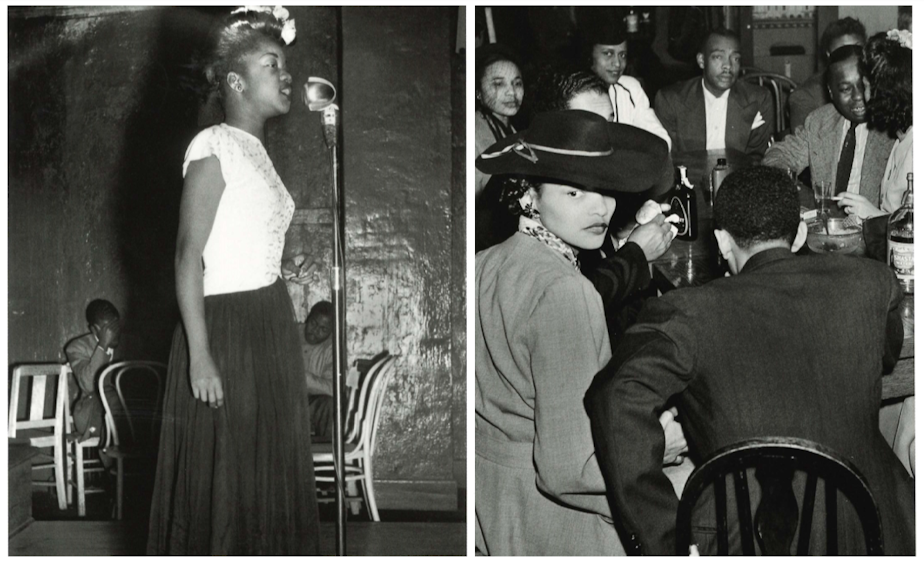

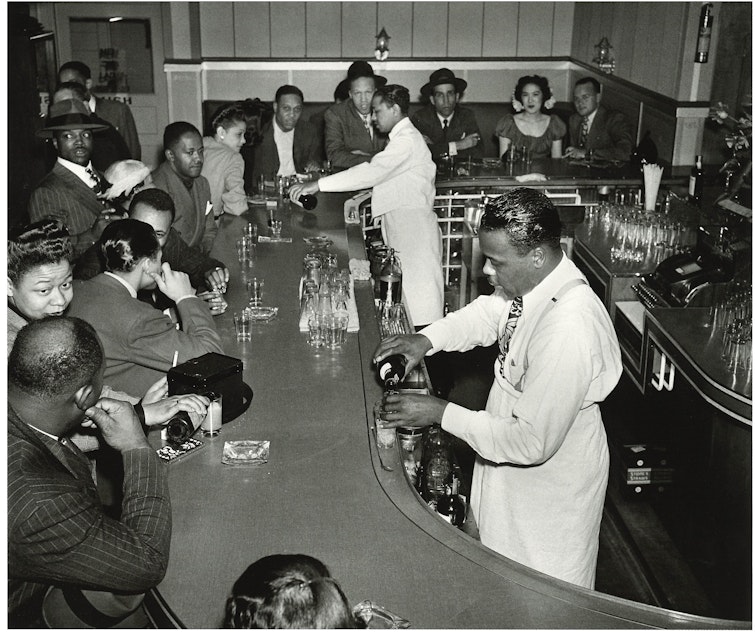

Smith shot photos of patrons at Seattle’s music clubs. He printed them up at home, then returned to the clubs the following week to sell the photos to the people he had photographed. He also made pictures of some of the African-American celebrities who came through Seattle: musicians, actors, even the champion boxer Joe Louis.

But Smith was equally likely to photograph friends at a backyard barbecue or the members of an African-American business association.

Sponsored

Do you know any of the people in these photographs by Al Smith? Tell us in this form.

Sponsored

Giske met Smith in the 1980s when MOHAI needed volunteers for an archival project. He says Smith became a fixture at the museum. It was only after Smith had been volunteering for a while that Giske found out Smith was also a photographer. And that he’d taken thousands of photos that he had stored in his basement.

“He was organized, kind of. He knew where things were,” Giske says, laughing. “But things weren’t thoroughly recorded or identified.”

So MOHAI, in conjunction with Seattle’s Black Heritage Society, put together a group of older African-Americans to help sort through some of the pictures and identify the people or organizations that Smith had documented. Giske estimates they managed to sift through about 800 images.