Meet the Seattle office buildings that could become your next apartment

The City of Seattle announced winners this week in its office-to-residential conversion competition.

Downtown has too much office space, and not enough housing.

But it’s not easy to convert old offices into apartment buildings. Practical and financial constraints mean that, at least in Seattle, such projects rarely pencil out.

And so, Mayor Bruce Harrell invited teams of architects and building owners to submit proposals along with advice on what the city would need to change to make those proposals move forward.

The projects submitted ranged from historic office buildings, including Smith Tower, to very plain-looking glass and steel office buildings from the 1960s.

1st place went to the Mutual Life Building, an office structure commissioned by Henry Yesler (owner of Seattle’s first mill, after whom Yesler Avenue is named), though he did not live to see it completed.

Were Yesler alive today, he'd probably find life within his building a bit of a disappointment.

"We walked through the building with the leasing people, and it's substantially vacant," said Rob Humble of Hybrid Architecture, part of the project team. "They're not getting any income, so to speak, from this building right now. And they were very receptive to the idea of converting this to housing."

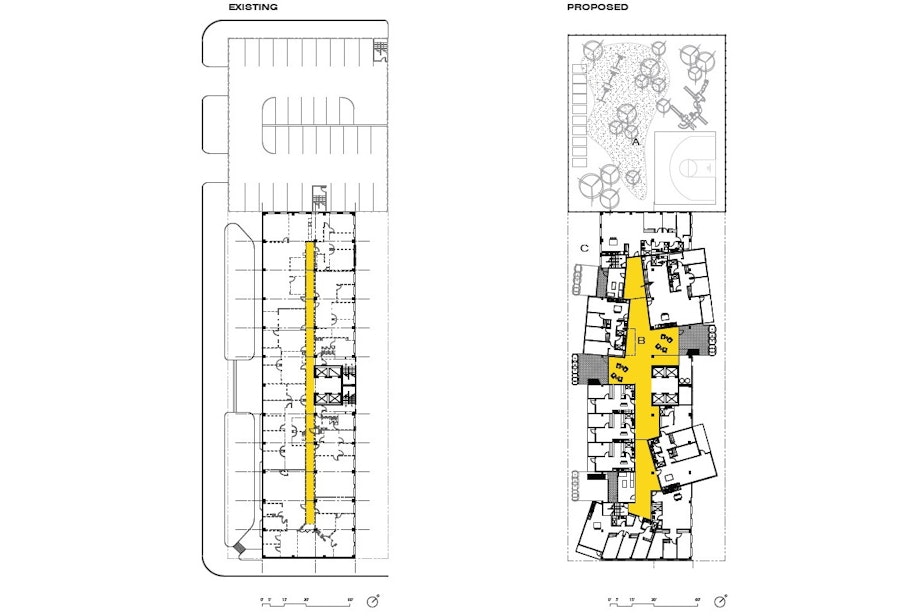

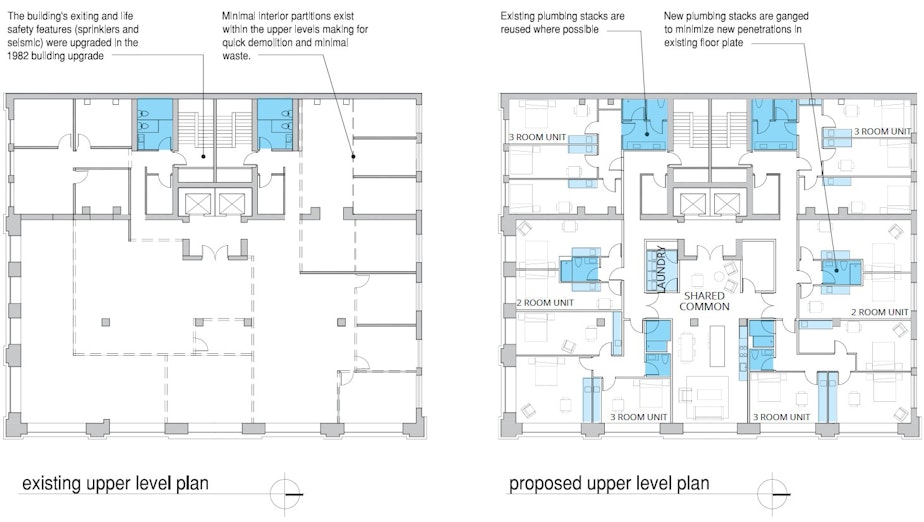

The design team proposed turning the building’s office floors into affordable housing for people transitioning out of homelessness. They leaned on a historic archetype, long phased out by many cities, known as “single-room occupancy hotels.”

In the renovated Mutual Life Building, residents would live in single rooms and share amenities like bathrooms and kitchens.

The strategy also helps address one of the core challenges with converting old office buildings to apartments: It gives you a way to use the dark interior space in the center of the floor, which is too far away from the window wall for most living spaces.

In this case, common spaces are put there, in large rooms with a window at the far end.

Another advantage of this strategy is that it’s easy to convert back to offices later, if the market shifts. That’s because the owner will not have scattered new bathrooms and plumbing across the floor in every apartment — bathrooms are consolidated in a few locations on each floor, not unlike bathrooms in an office. This was important to Humble, because who knows where the real estate market will go?

"We kind of think of these buildings as static in time," Humble said. "But this building was built in 1895 as two-story building. They added five floors to it, back in 1916. They converted it to housing in the 1960s. They did substantial remodeling, [turning it] back into office again in the 1980s. So these buildings really do have a have a very cyclical lifecycle."

And so, Humble added, its redesign should allow “for disassembly and adaptability, so that in the future, it can be reconfigured into some other use, if needed.”

2

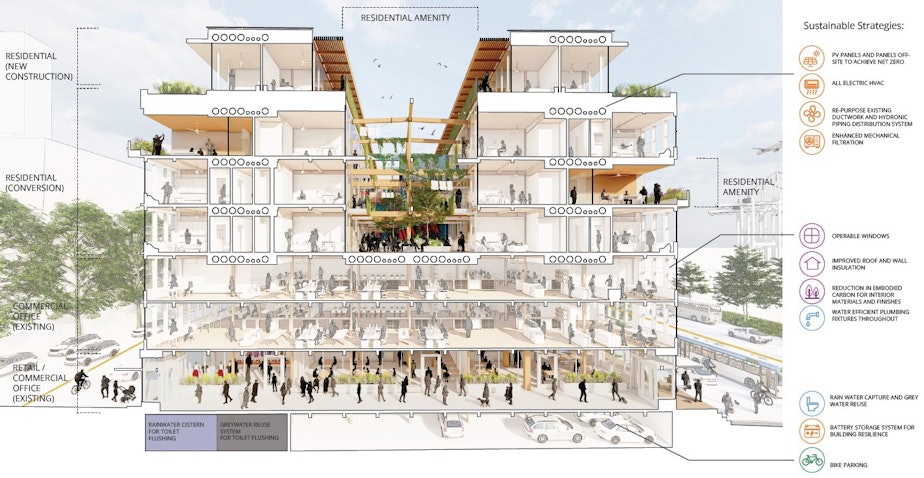

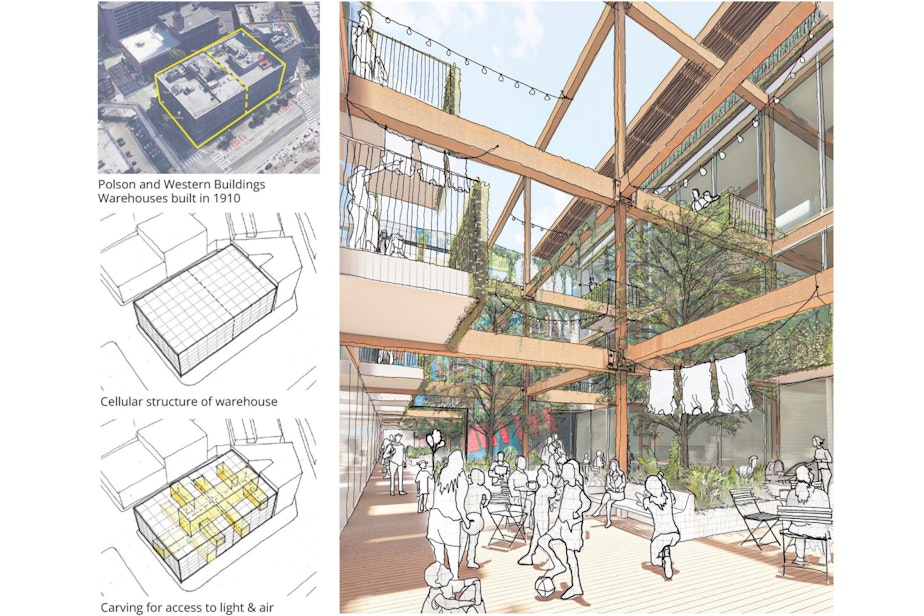

nd place went to some historic warehouses that have been office buildings for a while. These are near the waterfront and used to be in the noisy shadow of the Alaskan Way Viaduct before that came down.

In this project, the architecture firm Miller Hull offered another way to address the problem of the dark interiors of large buildings. They took a look at the structure behind the concrete warehouse façade — there was a grid of massive timber columns and beams holding up the floors. You find beautiful old-growth timbers in many of Seattle’s historic storage buildings. And within that grid of massive timbers, they started to carve out some of the interior space in the center and bring light into the center of the building that way.

“It is a legal requirement to have operable windows in bedrooms,” said Miller Hull’s Claire Rennhack, “but we came at this project from a humane standpoint where we felt it was important to provide light and air and social connection and amenity uses and green space access in an urban environment to all users of this building, whether you had a perimeter unit or whether you were in the center of the building.”

Historically, many larger office and residential buildings were shaped like letters of the alphabet, when viewed from above: A, B, E, U, P, and R. The thing you'll notice about these letter shapes is that they include holes. Translated into architectural form, these holes allowed light and air to penetrate the deep interior of buildings in the age before air conditioning and inexpensive artificial light. Many of those historic buildings filled those holes with elevators or stairways over time.

In this case, the building would be resurrecting that old technique to bring light into the bowels of a warehouse that never saw such light before.

This is not housing for people coming out of homelessness — it’s partly market-rate housing, which these days means high-end housing, and partly at the upper end of affordable housing, which some people call "workforce housing."

3

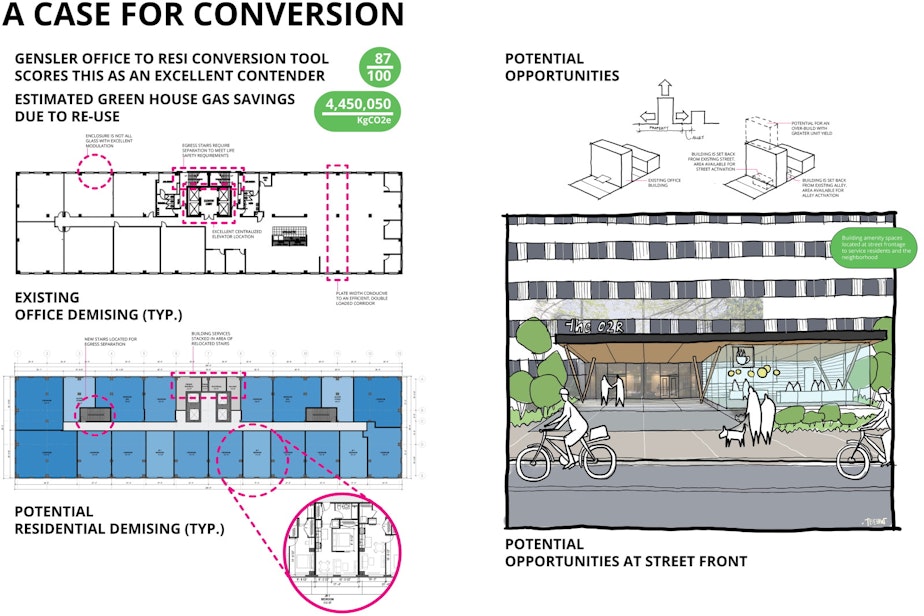

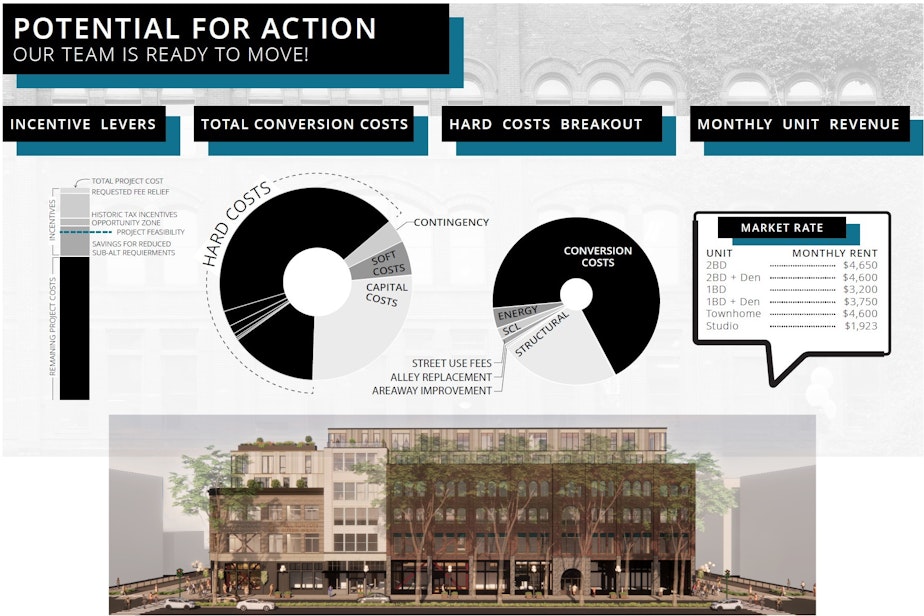

rd place went to a rather bland-looking post-WWII building. Gensler & Associates, the architecture firm, wouldn’t share the address — the owner didn’t want to freak out the current office tenants. But it’s a relatively narrow glass and steel box. Because it’s narrow, it doesn’t have the same problems of floor width that some of the other buildings did.

Gensler is a big firm, and they developed a tool that scores buildings according to how easily they can be converted to residential use. This non-descript building scored an 87 on that tool (so, a B+). But reusing the building rather than tearing it down would save almost 10 million pounds of carbon.

A member of the jury said this design team won third place because they showed how, by turning it into condos, they could afford to add new retail spaces to the street level, livening up what is currently a very dead looking streetscape.

Practical Barriers

One of the main practical barriers preventing these proposals from going forward is that when you change the way a building is used, once you’ve changed things enough, the building department considers those “substantial alterations.” And when you hit that threshold, you have to upgrade the building to current seismic codes, energy codes, and you have to meet the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

So in almost every case, designers asked for some relief from these modern standards.

Architects said, in terms of seismic codes, it’s not about dropping standards entirely, but in the case of buildings that were updated already a few years ago, why isn't that sufficient?

Rico Quirindongo, the director of the Office of Planning and Community Development, was wary of that approach.

“You’re on dangerous territory there,” he said.

But when it comes to modern energy code standards, Quirindongo said architects might find more wiggle room, especially when reusing a building actually reduces long-term carbon emissions.

Financial Barriers

You might be tempted to think that reusing an older building is cheaper. In fact, it’s often cheaper to tear the old building down and rebuild a new one from scratch.

Many of these projects asked for various tax breaks in order to make these projects pencil out financially. This is an area where the city has a lot of discretion.

Earlier this year, KUOW reported on how this kind of office to residential conversion is already happening in Tacoma. Projects are penciling out there because the market for office space is even more depressed, but there are also fewer fees on developers in those areas. Taken together, the threshold where the developers can make enough money to justify the project is lower in Tacoma.

RELATED: From offices to apartments and back: Could transformable buildings help revive downtowns?

But in Seattle, developers say they need tax breaks to make it work. The prevalence of office-to-residential conversions in Tacoma compared to Seattle supports this claim.

Even though some of these projects contained affordable housing, that requires a higher level of subsidy from the city. Many project teams figured they’d just get enough breaks from the city to squeak by, financially, and for that reason many of them assumed market-rate housing.

It's true that Seattle needs more housing at all income levels. A shortage of housing at any income level drives prices higher for everyone.

What happens next?

Mayor Bruce Harrell has promised to keep talking to these design teams. Quirindongo, the head of the city's Office of Planning, suggested that Seattle is not ready to make blanket changes to zoning rules or building codes to allow for all possible projects to move forward. But city leaders are interested in these projects, and will decide on a case-by-case basis how much it makes sense to relax the rules so that they can happen.

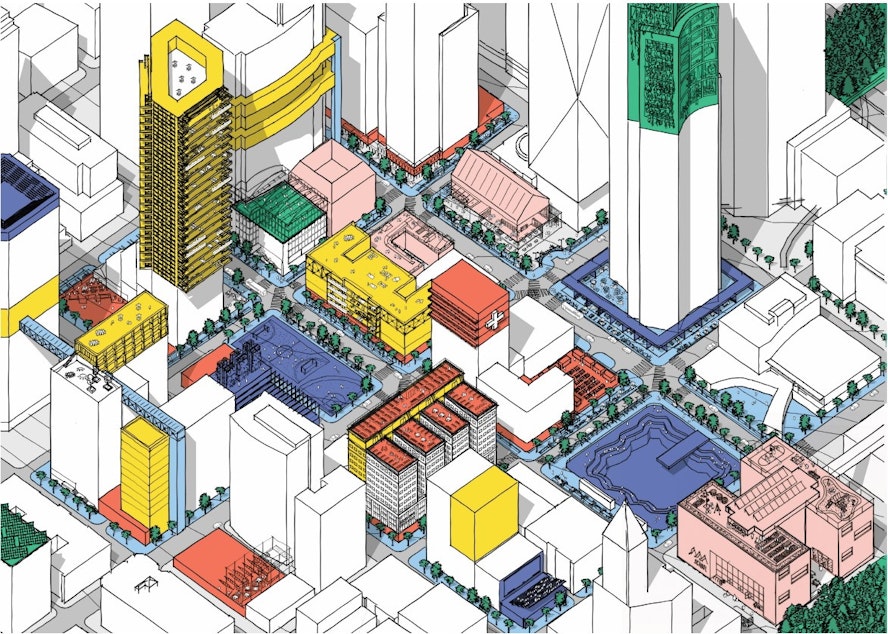

Thinking outside the box

At least two project submittals didn't include real buildings. Schemata Workshop used its submittal to demonstrate the importance of other amenities, like green spaces, grocery stores, schools, arts and culture. Architect Grace Kim suggested underused office buildings could be converted to these uses, too.

Graphite Design Group used its submittal to show how buildings could take advantage of existing structural components, but still break out of the rectangular glass and steel box shape associated with mid-century office towers.