What's in a weave? Native basketmaker and archeologist explore the stories baskets tell

To be chosen for a National Heritage Fellowship is to be recognized as a kind of national treasure.

The award is given by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and celebrates traditional and folk arts. Previous winners include folk and blues singers, woodworkers and potters. These are art forms that exemplify past and present cultures and communities.

That’s the kind of work recent NEA fellowship winner and master basket maker Ed Carriere has done for decades.

Carriere is a Suquamish elder and master basket maker in Indianola, on the Kitsap Peninsula. He's one of nine people recently selected for a Heritage Fellowship.

But Carriere's story begins with routine gatherings with his great-grandmother, Julia Jacobs.

"I probably never would've woven a basket if I hadn't have been raised by Julia," he said. "She was raised in Old Man House along with the Suquamish people and Chief Wahalchu."

That's where Jacobs learned the baskets of Suquamish life, the in-house soft baskets, cattails and sweet grass, baskets of bear grass and cedar bark. She taught by example, and Carriere learned by osmosis. He watched her gather the perfect limbs and roots from nearby cedar trees, soak those so they became malleable, and begin to weave.

"When I was 14 years old, I got brave enough to make one," Carriere said, looking out onto the beach where he learned to gather all those years ago. "It takes a lot of skill to split that limb in half, and split that root, and make a weave out of it."

Sponsored

Jacobs was particularly skilled in weaving the Suquamish clam gathering basket, which features perfectly sized holes throughout the weave that allow water and sand to seep through while keeping the clams in place.

In his late teens Carriere joined the military, serving for several years in Korea, before coming back and working at the nearby Naval Torpedo Station in Keyport. During this time, baskets went by the wayside for Carriere. Jacobs was the last person weaving this particular style of basket, as metal buckets had long replaced the woven alternative.

But as Carriere looked at his grandmother's baskets, he realized they represented something important.

"Julia was the last person to weave the clam basket, and she died in 1962," he said. "And I told myself, if I don't continue to try to really develop and bring this clam basket weaving up and bring it back, it's going to be completely gone."

Sponsored

Carriere began weaving again, following his memory of the techniques he was taught by Jacobs as a teenager. Over a dozen or so baskets he refined the practice, and basketmaking became a more realizable profession. He also began branching out to other tribes on the Olympic Peninsula, analyzing the unique stylings and weaves of their baskets, and even offering repairs.

"They have spruce root out there in the sand along the beaches, and we have cedar root here," he said. "I studied it and it was very similar to my clam basket."

That's how he met Dale Croes, a retired adjunct professor of archeology at Washington State University specializing in ancient baskets and wet sites (archeological sites found underwater). Croes was working at the Ozette Archeological site at Neah Bay, where researchers found centuries-old baskets perfectly preserved by a mudslide commonly referred to as the "Pompeii of North America."

"A Makah weave or a Suquamish weave or any different cultural community has their own identity through their basketry, their own designs," Croes said.

Sponsored

Carriere was using knowledge passed down for a least a dozen generations; Croes was studying techniques even farther back, ranging from 900 to 2,000 years ago. Carriere's clam basket weave, in particular, was something Croes had seen in other ancient baskets, but believed was no longer practiced by contemporary weavers. By meeting Carriere and understanding his techniques, Croes was able to decipher how these ancient baskets were woven, and how they were likely used.

"We were taught to look at stone, bone, and shell artifacts, and baskets are pretty foreign to us academically," Croes said. "You find stone, bone, and shell artifacts, but really rarely -- but we could find lots of baskets and cordage and wooden artifacts."

By sharing their respective knowledge, the two came up with an archaeological term called "generationally-linked archeology." This links modern day cultural specialists like Croes with ancestral basket-makers like Carriere, all with the scientific approach of archaeology.

"He's working with 4,500-year-old weaves," Croes said. "Statistically they link right up to what he learned from Julia Jacobs."

Sponsored

The prized work in Carriere's collection is a kind of "timeline basket." This is an homage to his work with Croes to understand weaving techniques over time, with the top of the basket featuring a 1,000-year-old weaving technique and the bottom being made in the style of a 3,000-year-old basket.

Together, Carriere and Croes have won recognition in the field like the National Society for American Archaeology (SAA) Award for Excellence in Archaeological Analysis. Their story and research is also told in the co-authored book "Re-Awakening Ancient Salish Sea Basketry: Fifty Years of Basketry Studies in Culture and Science."

Carriere said it’s nearly impossible to say how long it will take to make an individual basket. Between the time it takes to find the right materials, soak the limbs so they’re flexible, and hand weave, a single basket can take three months to complete. Each of those can sell from $2,000 to $5,000.

The NEA fellowship awards him $25,000, and he plans to use a portion of that money to teach new basket weavers. He's already taught several through the years, to help continue the centuries-long lineage of basket making.

Sponsored

"Basketry teaches us about our ancestors — not only, how they made that basket, but why did they make that basket?" Carriere said. "It teaches you their way of life. It tells a story. And so that was real interesting to me. I learned way more about my ancestors than I could have learned otherwise."

Listen to the interview with Ed Carriere and Dale Croes by clicking "play" on the audio above.

Modernizing the art of basket weaving

A visit to the Northwest Basket Weavers Guild

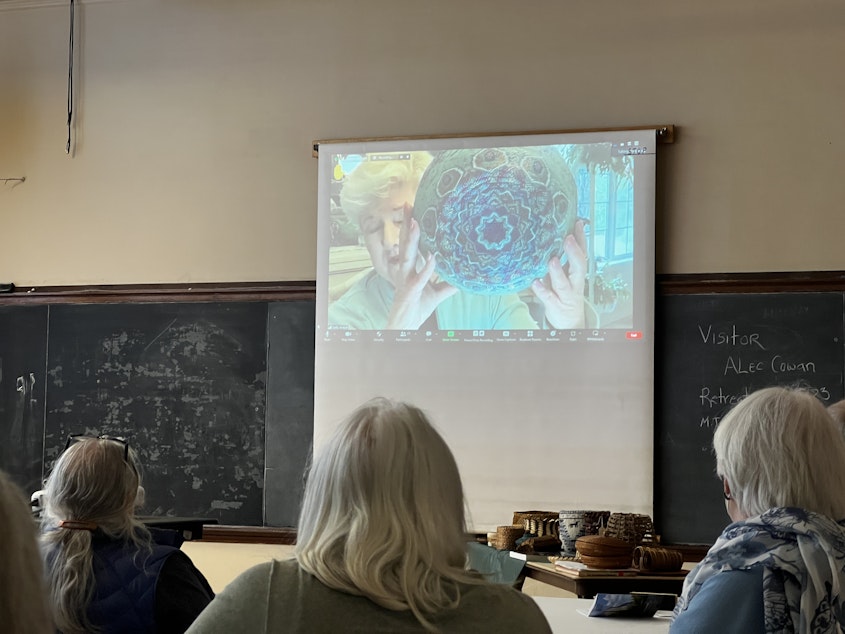

Soundside producer Alec Cowan attends a meeting with the NWBW to learn more about the ways hobbyists and experts are celebrating the past and future of basket weaving.

Carriere is a celebrity in basketweaving circles around the Northwest, and nationally, the Puget Sound Region is the place to be for basketweaving history and innovation.

In Seattle, the Northwest Basket Weaver's Guild meets every month at the Phinney Ridge Community Center. The guild has about 250 members, many of whom join by Zoom from places as distant as Arizona and the Northern Territories, in Canada.

This group is a combination of hobbyists and aficionados, professional weavers and locals looking to do something with materials they can find in their front yard. The guild supplies new weavers with the necessary tools for the variety of baskets the guild creates.

Guild president Karen Engel considers herself a hobbyist. For this meeting she's brought a small bottleneck basket and a larger soft basket with patterns in white and blue. Homages to the iconography and weaving styles of indigenous basket weavers are an important facet of the club, and Engel said the techniques she uses can be charted through her family to a Chehalis weaving technique.

Many members weave in the style of traditional makers like Carriere, using pine nettles, horse hair, and tree limbs for their baskets. But others have complex designs with deep layers of weaving and stitching, like one member's named "the reluctant peacock."

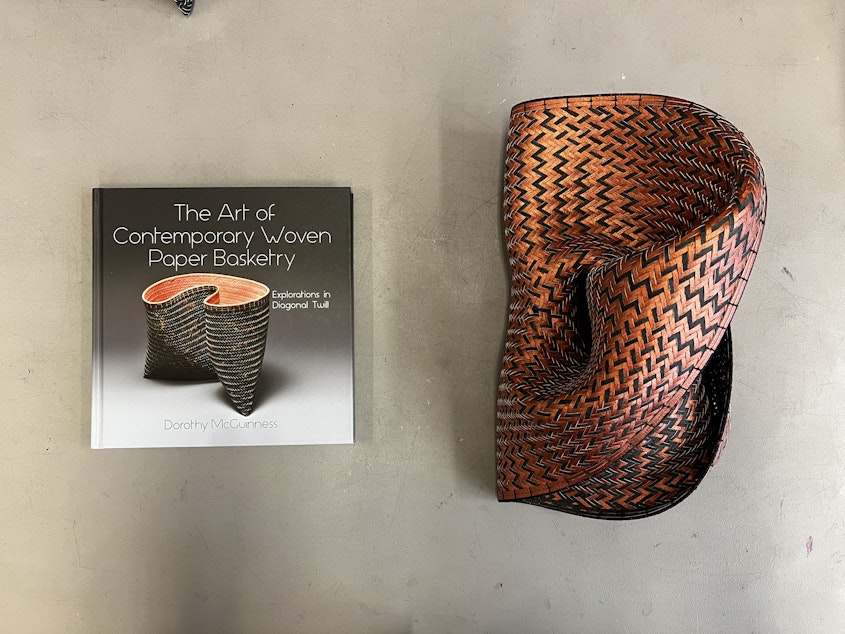

One weaver, named Dorothy McGuinness, uses strips of watercolor paper she slices with a pasta cutter. These are then twisted into three-dimensional abstract pieces of art. McGuinness' sculptural baskets can be found in museums around the country.

The special guest at April's guild meeting was Jill Green, a curator of baskets at the Burke Museum of Natural History, which houses 10,000 traditional baskets from all around the world. Similar to Croes, Green pieces together the shared stories of basket weaving across cultures and ages.

"I want to honor the maker," she explained during a slideshow of the museum's baskets. "I'm wondering about the journeys that it took, how many hands cans they pass through to get here. I want to know its secrets."

As Green cycles through slides of the Burke's most unique items, the room marvels at the weaving techniques present across time and cultures.

"The imbrication is so close to the start," Green said, as she points to the screen. "I mean, that just amazed me. Where's the taper? Looking closer, it's three rows below the rim."

There's a common language with baskets that connects present makers with past innovators. Why did this weaver choose to use an asymmetrical coil here? Why did they cover up the most beautiful part of the weave? Isn't it interesting how 3,000 years ago, they too were using pine nettles to bind the weave?

Baskets can feel like simple objects, but they also feel uniting, a shared story that strikes at something essential about the tools people use and the reason they use them. Looking at the variety of inspirations and styles, it can be easy to feel there's a beauty everywhere around — a hidden geometry of the world that just needs a weaver's touch to give it form.