A tale of two cities: August Wilson was born in Pittsburgh, but loved Seattle

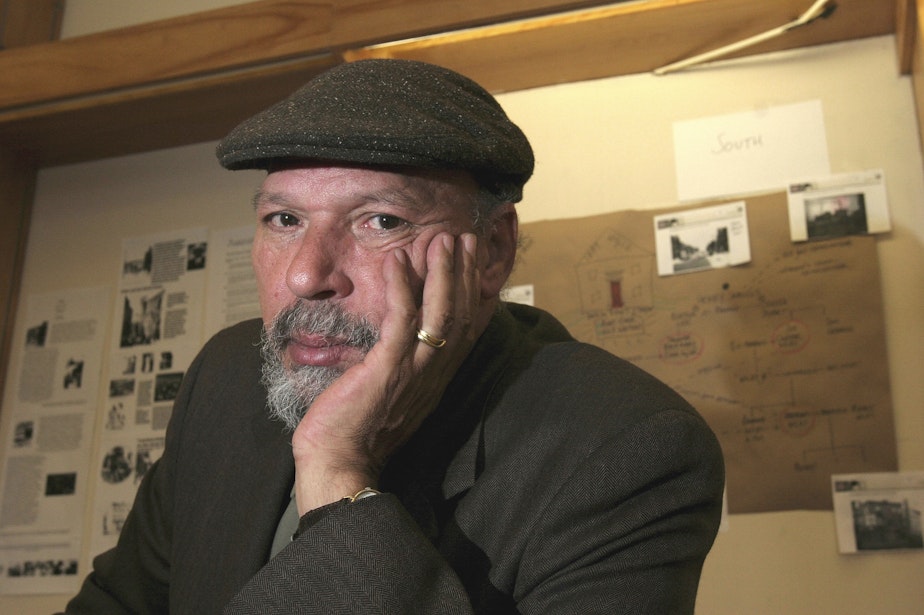

Nationally, August Wilson is known as an award-winning playwright, whose work captivated the nation with authentic storytelling that breathed life into characters portraying African American life and experiences throughout the 20th century.

His play "Fences," starring James Earl Jones, won a Pulitzer for Drama in 1987. In 2016, Denzel Washington produced, directed, and starred in a film adaptation that was nominated for an Oscar.

In early August, Wilson’s childhood home in the historic Hill District of Pittsburgh opened as a community center. The August Wilson House serves as a cultural hub for artists offering residencies, gathering spaces, and programming focused on fostering the next artists to emerge from Wilson’s former neighborhood.

This project exemplified Wilson’s impact on the culture of Black actors.

“Denzel Washington and a number of his colleagues are our main benefactors,” explained Denise Turner, chief executive and board president of August Wilson House. “He raised $5 million for this project. We have Denzel and Pauletta Washington, Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, Samuel L. Jackson and his wife LaTanya Richardson Jackson, Laurence Fishburne, Antoine Fuqua, and Shonda Rhimes.… These are the benefactors who allowed us to really get this project off the ground.”

While Pittsburgh celebrates its native son’s legacy and dedicates his former home to the up-and-coming artists in their community, we must remember that Wilson had an additional home, a second city that was impacted and uplifted by his work – Seattle.

Sponsored

Wilson moved to Seattle in 1990. The American Century Cycle – Wilson’s famed series of 10 plays detailing and chronicling the experience of Black folks in America during each decade of the 20th century, was primarily set in Pittsburgh. But many of those plays were written in Seattle.

“So much of his life really was in Seattle,” said Constanza Romero, who was married to Wilson from 1994 until his death in 2005. “That's where we had our daughter, where we set up our home, and in our basement is where he wrote so many of his plays.”

During the 15 years Wilson lived in Seattle, he established a deep connection with the Seattle Rep. When Wilson wrote his plays, they would be produced by the Rep and people in Seattle would have a chance to see these plays before they made it to Broadway.

But Wilson was more than just a writer who landed in Seattle to work. He was a resident, a community member, and a friend.

“We would discuss everything that was happening in America,” longtime UW professor and novelist Charles Johnson said.

Sponsored

Wilson and Johnson were best friends.

“With Black America, with the arts, with our families, with our agents and our representatives, and, you know, the time would literally just melt away,” Johnson recalled.

Johnson met Wilson after a performance of "Fences." After the show, he said he approached Wilson, who had just moved to Seattle. The two decided to meet at the Broadway Bar and Grill for dinner. This first dinner sparked a friendship that lasted well over a decade. The two would often meet for dinner at 7 p.m. and talk until they were asked to leave the restaurant at 2 a.m. Then, they would go to the IHOP on Madison to continue their conversations until early morning.

“You know, he was a brotha’,” Johnson said describing Wilson. “If I could just put it that way, you know, he was a straight up brother who cared about Black people. Black America. And, you know, that's part of his inheritance from the late 60s, you know, in the Black Arts Movement.”

Johnson wrote "Night Hawks," a collection of short stories that includes a story about the nights he spent with Wilson. In that story, the title story from the book, Dr. Johnson points out that both he and Wilson inhabit a particular space in African American history where they “belong to an in-between liminal generation that remembered segregation yet was also the bridge to the post-civil rights period and beyond.”

Sponsored

The significance of the era that birthed Wilson manifests in his connection with education and his journey to becoming a writer. According to Johnson, Wilson recalled attending a recently integrated school as a youth, where he was once sent home in a taxi cab after being beaten merely for existing, and in those moments he never quite understood why. Then, in the ninth grade, Wilson was accused by a Black teacher of plagiarizing a 20-page essay titled “Napoleon’s Will to Power.” Wilson refused to apologize for the false accusation and dropped out of school.

After that, Wilson would spend his days in the library reading, because to him, he “dropped out of school, not out of life.” It was in that library that Wilson decided he would be a writer. He once told Johnson, who eventually wrote in "Night Hawks," that a prostitute told Wilson, “If you want to be a writer, then you better learn how to write about me.” And that’s exactly what he did.

Wilson’s upbringing in the late 60s was a heavy influence on his work. Benjamin Moore, managing director at the Seattle Rep when Wilson was producing plays, ponders why Wilson moved to Seattle in the first place.

“It was always a curious choice, given a lot of his writing about race and Blackness and, and his ferocious pursuit of protecting a movement in the country that was challenged, with respect to African American theatre,” Moore said.

But there was a simple reason why Wilson chose Seattle.

Sponsored

In Seattle, Wilson could blend in without being bothered in ways that were not possible in New York and Los Angeles. In those cities, he was often recognized. While living on Capitol Hill, Wilson could spend time inconspicuously sitting in public spaces listening to real people having natural conversations.

Moore remembers joining Wilson in one of his go-to writing places.

“I was sitting in one of his coffee shops. And he was telling me about 'King Hedley.' And he was writing it at the time," Moore recalled. "And he was talking about how, how he listens for the characters that he's writing. And that process was mystifying in a way. It's kind of like, what people do who paint landscapes. It’s layer upon layer, and what comes out is coming from the artist’s mind, and it sort of emerges on the surface of the canvas. And that seemed to be similar to what August was describing.”

Somewhere, in the midst of writing award-winning plays, spending days in cafes and nights in restaurants, Wilson was also able to find time for a true Seattle past-time.

“He loved to barbecue meat,” his wife Romero said. “And we were saying, 'It's not going to be a good day to barbecue because it's raining.' And you know, by the fourth day or so, we basically said together, ‘Heck, you know, it's always going to be raining in Seattle. So, we're going to barbecue now.’ And you know, who cares? We're barbecuing in the rain.”

Sponsored

Pittsburgh is where Wilson was born. But Seattle is the place he chose to call home.